Okay, so let’s say in this abstract sense that the line that we’ve drawn represents an electron moving through space. Furthermore, we usually use straight connections because what we care about is the qualitative relationship between the endpoints and not the particulars of how a particle got from one endpoint to the other. And in fact, many times Feynman diagrams are represented without axes at all. This is why we haven’t put scales on our axes. To show a particle on such a graph, we simply need to draw a line that represents that particle’s position at each time.Īt this point, it’s worth stressing again that we only care about the qualitative relationships between the various positions and the various times. Since we’re interested in the spatial and temporal locations of our particles, we’ll represent them on a graph with axes of position and time. And that’s why we’re using this interaction to introduce the rules for Feynman diagrams.

#ELECTRON CAPTURE FEYNMAN DIAGRAM VERIFICATION#

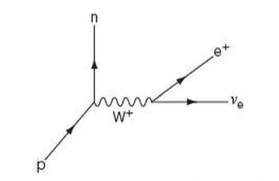

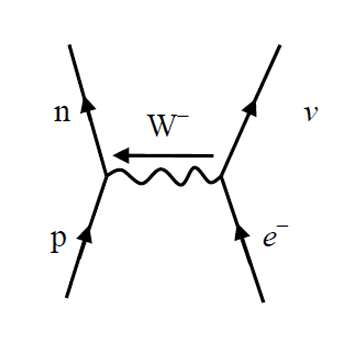

This verification is especially easy for electron–positron annihilation because the interaction is so simple. Okay, so to actually draw a Feynman diagram for this interaction, we need to be able to represent the particles, their spatial and temporal locations, and verify that the mechanism pictured is a valid one. The function of an individual Feynman diagram is to show one such valid mechanism. It turns out that for any valid nuclear equation, there are actually infinitely many valid mechanisms that form the products from the reactants. As an example of the alternative, the equation electron interacts with positron to form proton and antimuon has no valid mechanism, since this equation actually violates three conservation laws: charge, lepton number, and baryon number. This implicitly tells us that there is at least one valid mechanism that actually forms the products from the reactants. The second piece of information implicit in this equation is that the reactants actually interact to form the products. Nor will they annihilate if one passes through a position in space and the other passes through that same position but only several seconds later.

An electron and a positron that are flying apart from each other won’t annihilate. What’s really important is the qualitative statement that we’re making. For example, weak interactions tend to take place on much shorter length scales than electromagnetic interactions. How close is close? It depends on the scale of the interaction. When we say our reactants interact, we are implicitly saying that our reactants get close enough together in space and in time for the interaction to occur. This equation also carries with it some implicit information that we’ll need to spell out to properly draw a Feynman diagram. To borrow language from the study of chemistry, we can think of this equation as a set of reactants interact to form a set of products. Here, the Greek letter lowercase 𝛾 is used to represent photons. Written as a nuclear equation, we have that an electron interacting with a positron can form a photon. This diagram is one of several diagrams, all of which have the same basic shape that form the basis of quantum electrodynamics. In this lesson, we’re going to learn how Feynman diagrams represent particle interactions and also draw diagrams corresponding to some common scenarios.īefore defining formal rules, let’s understand the basics using the Feynman diagram for electron–positron annihilation. If I assume a 3 vertex diagram and hence a $4\pi \alpha^3$ dimensionless constant then I obtain a good estimate for the thickness of the Sun's photosphere.Feynman diagrams are simple graphical representations of particle interactions that underlie deep calculations about fundamental physics. I've published this work, which is still being developed, on my website. Some background to the question: I'm trying to determine the cross-sections for photon absorption of Hydrogen Balmer lines, specifically I'm trying to link these cross-sections to the Einstein absorption/emission rate coefficients. If my 3 vertex diagram is correct then I guess the fine structure constant cubed will be in the mix but are there any other numeric constants? What are the dimensionless factors involved in the cross-section for the process. The virtual photon is finally absorbed by the nucleus of the absorbing atom at the 3rd vertex. Is it described by an incoming photon and bound atomic electron interacting at one vertex with an outgoing virtual electron which then, at a second vertex, emits a virtual photon and a real bound excited electron. What is the simplest Feynman diagram for photon absorption by an atom?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)